A quick fix for Birmingham children’s social services will be neither quick, nor a fix

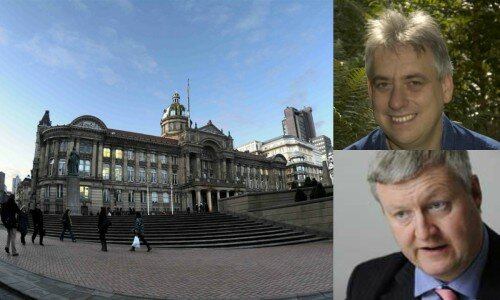

Andy Howell’s thoughtful Chamberlain News article analysing the deep-seated problems faced by Birmingham children’s social services deserves to be taken very seriously by those charged with turning around this failing department.

It should be read by politicians and officials alike, not just because, as deputy council leader in 2000, Howell had a top table seat at the start of the long decline of social care, but also because many of the points he makes hit directly to the heart of the matter. His considered piece did not to take a pop at the last council administration or the current national coalition government. As a political animal to his core, Howell chose not to play party politics on this most important of issues, but focus instead on improving a critical public service.

In particular, he sheds light on something that I had never considered before, but must surely be pertinent to any sensible discussion about the future of services for vulnerable children.

Howell makes a comparison with Birmingham’s appallingly poor schools in the 1990s, which were transformed following a concerted effort by the city council and the inspired appointment as chief education officer of Prof Tim Brighouse.

What Howell goes on to say merits repeating: “There is one big difference between children’s services now and Birmingham’s education service then. In the 1990s the Birmingham’s education service was a massive concern of the articulate middle class and the pressure that they put on the council simply could not be ignored.”

The more you think about this statement, the more obviously true it becomes. The performance of schools is the classic middle class cause celebre. Good GCSE results, good A-level results, get into a good university, these are meat and drink issues for the sharp-elbowed aspirers who want their children to succeed in life.

Children’s social care, on the other hand, who really gives a damn? By its very nature, as Howell points out, this is a service that is “most focused in those disadvantaged communities that are too easily marginalised and who are often simply not able to shout loud enough”.

For most people in Birmingham, and for most of the time, the performance of children’s social services simply isn’t on the radar. It only becomes an issue when something goes horribly wrong, the appalling death in 2008 of seven-year-old Khyra Ishaq at the hands of her mother and partner, for example.

A subsequent Serious Case Review found that the death could have been prevented had it not been for stunning incompetence by all of the ‘caring’ and public agencies, including city council social workers and education officials who simply didn’t understand the powers they possessed to demand to check on Khyra, who was being starved to death.

Politicians locally and nationally tend to move into ‘something must be done mode’ when this sort of thing happens, and there is little more dangerous than a politician reacting to media pressure to ‘do something’ by responding with an ill-thought through quick fix. This usually turns out to be something that is neither quick nor a fix.

This brings me to another of Howell’s central points. I call it the headless chicken syndrome, although Mr Howell is naturally too diplomatic to use such a crude analogy. It is undeniably true though that a grisly child death generally results in reorganisation of social services at a level pre-determined by the scale of national and local media criticism heaped on to Birmingham.

For a Khyra Ishaq type of event, a wholesale clear out of senior and middle management is generally the council’s default response. And since there have been a number of such events since 2000, the children’s social services department has been pretty much in a permanent state of upheaval.

Mr Howell puts it like this: “Critics of the city argue that the real problems of the council are to do with inconsistent and ineffective management combined with an internal culture of complacency and denial.”

I would add to that an obsession with short-termism and a failure to give senior managers time to do the job and make a difference.

A general pattern has emerged over the past decade. New managers arrive and identify the problems, which are well known. These include a shortage of social workers, a lack of good social workers, inconsistent performance, pockets of excellence and pockets of failure, the inability of public agencies to work together and share information as well as the incredible demands placed on social services by a level of social deprivation not found on such a scale in any other city.

The new managers have a plan, which is usually the same plan re-packaged and re-presented. This involves identifying ‘at risk’ children at an earlier age and intervening with support before it is too late. The aim of the plan is to develop a seamless children’s services organisation offering support from cradle to the first job. But the plan can only work if all of the agencies – council, police, schools, GPs, hospitals – sign up to it, and really mean it when they do.

Naturally, the new managers always take care to stress that it will take a long time to turn around a department with problems as complex as Birmingham children’s social services. Unfortunately, time is a commodity perpetually in short supply among Government Ministers and council leaders.

The last director of Birmingham children’s services, Peter Duxbury, lasted a mere 13 months before leaving. His predecessor, Colin Tucker, managed almost two years before leaving after council leaders said they weren’t satisfied at the rate of progress.

By all means set up an independent commission to examine the problems surrounding children’s care, as Mr Howell suggests. But don’t expect anything very new to emerge, since the problems facing Birmingham and the solutions to those problems are well known.

The best thing that the politicians can do for Peter Hay, the new director in charge of social care, is to tell him they expect and hope that he will still be in the job in 2020. And on top of that, they must resist the temptation to micro-manage Mr Hay. Back him, and let him get on with the job.

Similar Articles

Eric Pickles announces £21m regeneration boost for Birmingham and the Black Country 2

Communities Secretary Eric Pickles, who is best known for slashing council budgets, has shifted into

£3,000 ‘golden hello’ payment plan for Birmingham social workers hits a glitch 6

A plan to make £3,000 ‘golden hello’ payments to social workers will have to be revised

Booming London makes case for devolution, but whose fingers are pulling the strings? 6

The debate about the size of London and its stranglehold over the UK economy has

Commissioner Jones and Andrew Mitchell clash over police stop and search powers 4

West Midlands Police Commissioner Bob Jones is at risk of upsetting some of his Labour

London basks in economic boom, while Birmingham ‘punches below its weight’ 8

Britain’s economic recovery is dominated by job creation in London, leaving cities like Birmingham, Manchester

Need to clarify a few things here. Colin Tucker was not a ‘predecessor’ of Duxbury except in the sense that he was employed by the Council before him.

Duxbury was Director of Children’s Services and followed the central government suggested Eleanor Brazil who succeeded Tony Howell. it is with Howell that these problems originated following the ‘integration ‘ of education and children’s social care departments following the Lamming report into the death of Victoria Climbie. There were intrinsic problems immediately. Peter Hay was transferred to adult social care and Howell (Tony) took responsibility for this new department even though he wasn’t up to even controlling education. Head Teachers didn’t respect him and staff tired of his embarrassing initiatives (“Imagine a City” and the like) with excruciating presentations. it was only the funding initiatives from the Labour Government that papered over the obvious cracks.

When Khyra Ishaaq died Tony Howell should have resigned (as suggested in Lamming report) but instead he limped on, appointing Tucker as a response to lessons that, as always, needed to be learnt.

Why I think #bcc should take @Andrew_Howell’s @ChamberlainFile article on children’s social services seriously

@paulmdale picks up on piece by @Andrew_Howell for @ChamberlainFile on fixing Brum social services