All systems go for metro mayors as Devolution Act gets Royal Assent

Eight months after its first reading in the House of Lords, the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act has received Royal Assent and has passed into law, writes Paul Dale.

There were plenty of commentators who thought the Government’s flagship devolution bill might struggle to get through Parliament and could even fall victim to time-consuming amendments from MPs on all sides of the House who view the metro mayor and combined authority model with deep suspicion.

But in pretty much record time, the measures described by Chancellor George Osborne as a “devolution revolution” have been approved with remarkably little alteration.

The main purpose of the Act is to:

- Pave the way for elected mayors to cover and chair a combined authority area

- Allow the devolution of functions, including transport, health, skills, planning and job support

- Ensure that local enterprise partnerships play a leading role in combined authority governance

- Enable the creation of sub-national transport bodies which will advise the Government on strategic schemes and investment priorities in their own area.

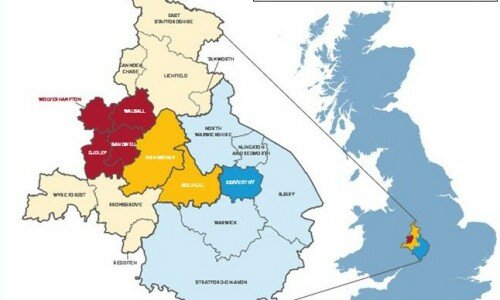

One obvious impact of the Act will be to speed up the creation of a Midland-wide transport body, similar to Transport for London, to run local train, tram and bus services.

Midlands Connect, a shadow body consisting of west and east Midland councils, LEPs and transport authorities as well at Highways England and Network Rail, is investigating better transport links between Birmingham, Nottingham and Derby.

Midlands Connect can now move to a statutory basis and will play a major role in improving transport links across the region, from west to east.

Even before the Act reached the statue books the devolution process has moved ahead.

The West Midlands combined authority, chaired by a metro mayor from 2017, is one of seven English devolution deals already approved by Mr Osborne. The others are Greater Manchester, Liverpool city region, Tees Valley, the North East, Sheffield city region and Cornwall.

In each case, apart from Cornwall, council leaders had to agree to have an elected metro mayor in order to obtain the devolved powers and budgets offered by the Chancellor.

During the passage of the legislation through the Lords and Commons, Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs attempted a variety of methods to tone down mayoral powers and to make the imposition of a metro mayor subject to approval by local referendums.

In its final form the Act gives powers to the Secretary of State to remove councils that object to the introduction of a mayor or the transfer of powers from a combined authority.

The Bill’s original drafting allowed only one objecting council to be removed from a combined authority but a late amendment will allow an elected mayor to be put in place and devolution to proceed where one or more councils are opposed.

Other amendments will enable elected mayors to delegate functions specified in an order from the Communities Secretary and will allow mayors to exercise their functions jointly with other authorities or combined authorities.

Now that the Act is enshrined in law it will be possible for non-constituent members of combined authorities, the shire districts in the West Midlands’ case, to have equal voting rights with the metropolitan councils.

Communities Secretary Greg Clark was at pains to stress during the Bill’s third Commons reading that no councils will be forced to become combined authorities or have a metro mayor.

Mr Clark described the Bill as a bottom up reform driven by local opinion, not imposed by Westminster.

He said:

The Bill allows reform where civic leaders and councillors desire it. It is a Bill that proceeds from the bottom up, rather than the top down. That makes it a novel Bill in the history of legislation concerning local government that this House has considered.

It is a Bill that does something that previous Governments have baulked at, which is to transfer deliberately powers that Ministers and Governments have held and exercised in Westminster and Whitehall to authorities across the land. The insight of the Bill is that those objectives can be achieved together if local people are given their voice and allowed to set their arrangements in their own way.

The breakthrough is the recognition that not all places need to be the same. One of the glories of this House is that we know that each of our constituencies is very different from the others.

No place is the same. A world in which policy is identical in every part of the country is a world in which policy is not well set for particular parts of the country. Each place has a different history, different strengths and different capacities.

Mr Clark claimed the Bill would “allow the often latent potential for economic growth across all parts of the country to be better unleashed” and bring businesses into close collaboration with their local authority leaders.

The seven devolution deals were only the start of a longer process, he said.

It is important that we have devolution right across the country. We started with cities, but the enthusiasm in counties and districts right across the country has been very palpable.

Alexandra Jones, Chief Executive of Centre for Cities said:

The granting of Royal Assent for this Act is a critical milestone in the devolving of substantial powers to city-regions across the country.

In the short-term, it will enable the devolution deals already agreed for Greater Manchester, Sheffield city-region, Merseyside, the North East, the West Midlands and Tees Valley to be delivered in the coming year. It will also allow for the finalising of similar deals with other city-regions across the county.

But the passing of the Bill should be the beginning of the devolution process, not the end. Over the longer-term city-regions will want to build on the progress made so far, and emulate their international peers, by taking on greater control over, and responsibility for, money raised and spent in their area.

Labour, although broadly supportive of devolution, claimed the Bill did not go far enough.

Shadow Communities Secretary Jon Trickett said the Bill was a top-down model of devolution that insisted on imposing metro mayors on cities even where electorates had recently rejected the idea.

Mr Trickett said:

We have tried to be positive, but, despite the Bill being a milestone, we feel it has been scarred by timidity, and we are frustrated by the lack of ambition.

It appears that much of the Bill was shaped by No. 11, rather than being created in the great cities, counties and villages of England, and it simply does not match up to our devolution achievements in Scotland, Wales and London.

Our amendments—for example, those decoupling a mayor from the ability to secure devolution, as well as those on finance offering stability to local councils, on multi-year funding and on the provision of greater fiscal autonomy—would have helped make local government more autonomous, more powerful and more relevant to local communities.

The truth is, however, that every single one of our amendments, which were designed to extend powers to local communities, was rejected by the Government. Not one was accepted—and that is the truth of it.

Similar Articles

PM: gave unlawful advice; frustrated Parliament

"Scenes." As young people would say, writes Kevin Johnson. "Unlawful." "Unequivocal." "Historical." These words are not,

WMCA: Nothing to see here…move along

As the Prime Minister prepared to address leaders ‘up North’ gathering for the Convention of

HS2: new driver needed

Is the Oakervee Review "welcome", "frustrating" or the end of the line for HS2, asks

Dawn goes Down Under

It might appear that Birmingham city council changes its chief executives more regularly than its

Hezza: Give Metro Mayors greater powers to deliver housing, skills and jobs

Britain’s metro mayors should be given greater powers over housing, schools and jobs to truly