Remembering Kennedy: the Myth of Camelot

On the 50th anniversary of his assassination, lead blogger (and amateur Kennedy scholar) Paul Dale recalls his personal memories of the day and assesses JFK’s legacy.

Details of the shooting and death of President Kennedy reached Britain in the evening of November 22, courtesy of a television newsflash. It was an event that I remember vividly, even though I was only seven at the time.

There was inevitably something rather thrilling about a newsflash half a century ago in the days before the internet, rolling 24-hour news programmes and mobile phones would keep us instantly informed about current events.

Newsflashes happened extremely rarely. The news agenda had not been sensationalised or dumbed down in 1963. Tragedies were just that, and did not extend to the activities of professional footballers and showbiz ‘celebrities’.

The first indication of JFK’s death would have been the sudden disappearance from television screens of, say, Coronation Street, with a doom-laden announcement that “we are interrupting this programme for a newsflash”.

Then, the briefest of delays which served only to heighten tension before a newsreader would appear sombrely dressed on a grainy black and white screen against a dark-curtained backdrop to make a brief and measured, announcement.

I recall the look of shock, and perhaps fear, on my parents’ faces. My mother certainly cried. Even my father appeared emotional which, given his background as a wartime Regimental Sergeant Major in the Far East who had seen some terrible things in his life, was remarkable.

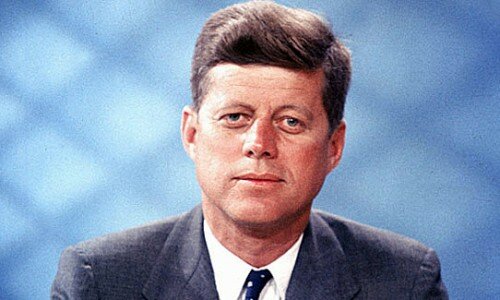

The dawning realisation that this young, handsome, charismatic, leader credited only a year before with standing up to the Soviets and seeing off a nuclear conflagration, had been assassinated in the open streets of Dallas was too much to bear for many people, and remains so today.

An entire conspiracy industry quickly took off intent on ascribing Kennedy’s death to the KGB, the CIA, the Cubans, the Klu Klux Klan, the Mafia, almost anyone other than the lone assassin responsible for the outrage. In fact, America’s reluctance collectively to accept that one rather nondescript man armed with a rifle could have shot and killed a president goes a very long way towards explaining the Kennedy mythology today.

A little over a year later, I was taken to Pangbourne station in Berkshire to join scores of mourners waiting with heads bowed for the funeral train bearing the coffin of Sir Winston Churchill to pass on its way to Bladon. The silence, and the tears, of those gathered on the platform remains with me to this day.

In a short period of time, therefore, the world had lost two leaders who were symbolic of their time. Churchill, the saviour of Britain during the Second World War, and Kennedy, the great hope for freedom during the post-war realignment of the super powers.

At least, that’s the way most of us like to recall Churchill and JFK. The brutal truth, however, is that both had serious character flaws and were very much ‘of their time’. That is to say, were either to be reproduced today, possibly neither would survive the microscope of blanket media intrusion into their political achievements and private lives.

Churchill was an impulsive adventurer who, like Kennedy, could rise to stirring oratory. He’d experienced life at the front end of war, in South Africa during the Boer campaign, and in the First World War. Kennedy, too, had his ideas shaped by conflict, in the Second World War.

Both wrote best-selling books. Churchill made a fortune from his History of the English Speaking People’s, although the extent to which the work was actually his own remains a matter for debate. Kennedy penned Profiles in Courage, and won the Pulitzer Prize for it, although it was later alleged that most of the manuscript was written by his speechwriter, Theodore Sorenson.

Churchill, as evidenced by the diaries of colleagues, consumed vast quantities of alcohol during the Second World War and was rarely entirely sober. Kennedy, meanwhile, was a sexual predator who built up a long list of conquests including Marilyn Monroe, whom he reportedly shared with his younger brother, Robert.

JFK famously stunned the Edwardian-born British prime minister Harold Macmillan by confessing: “You know Harold, I get a migraine if I don’t have sex every day.” Macmillan recalled in his diaries that, for once, even he could not think of a suitable reply.

Churchill wasn’t a great prime minister. A unique war-time leader who, arguably, helped save the west from Nazi domination, yes. But a lousy peace time leader who ought to have retired long before he again became prime minister in the 1950s when he was into his 80s.

Was JFK a great American president? This is a question that most people will feel is superfluous such is the power of the Camelot/Kennedy mythology. But the truth is his presidency never quite matched up to the promise of the inauguration ceremony’s soaring cadences.

His words were a masterclass in powerful oratory, and many phrases are remembered today. We become misty-eyed when recalling ‘ask not what your country can do for you’ and ‘the torch has passed to a new generation’, but it was all down to Sorenson’s speechwriting genius really.

Any appreciation of Kennedy’s performance has to come with the caveat that he served for less than three years. He might have won in 1964. He might have improved with age. But we can only judge against what actually happened.

A botched CIA-backed invasion of Cuba – the Bay of Pigs fiasco – probably served to bolster the nerve of Soviet president Nikita Khruschev, who convinced himself that Kennedy’s weakness meant that the Russians could get away with placing nuclear missiles on the communist-led island.

The Cuba Crisis is generally regarded as Kennedy’s finest hour. But the emergency was only resolved when Kennedy entered into a secret bargain with Khrusechev and agreed to withdraw American missiles from Turkey if the Russians turned back ships carrying nuclear warheads to Cuba. It later transpired that the offer was not as selfless as it may have seemed. The Turkish missiles were already obsolete and being replaced by Polaris submarines.

This arrangement was not disclosed to the world until 1971. As far as Americans knew in 1962 the Russian withdrawal had been the result of Kennedy standing firm against all the odds, slugging it out eyeball to eyeball with Khrusechev, who apparently had crumbled under pressure.

After Cuba, Kennedy became sucked into a ‘war against communism’ in Vietnam where he twice authorised the tripling of American troop numbers in South Vietnam. The conflict lasted until 1975 and would eventually cost 58,000 US lives as well as the deaths of an estimated three million Vietnamese and Cambodians.

On the issue of civil rights, Kennedy talked a tough game about ending segregation in southern states, but when push came to shove was slow to intervene to tackle some of the more outrageous examples of racial discrimination. He turned down an invitation to attend the civil rights march on Washington in 1963 where Martin Luther King made his ‘I have a dream’ speech, claiming that the event would inflame tensions and damage the passage of a civil rights bill. His push towards civil rights legislation did finally pass into law in 1964, a year after his death.

On the matter of social policy, Lyndon Johnson achieved far more than JFK and managed to secure the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. His Great Society programme began the process of edging America very slowly towards a form of state social aid, in particular medicare. Fifty years later, LBJ’s efforts to help the needy are still being pursued by President Obama, and medicare is proving just as controversial.

Johnson was barely tolerated by the super-rich, patrician Kennedy clan, who regarded him as an unsophisticated hick to be tolerated only because of the electoral support he could muster in southern states. Yet history surely shows Johnson to have been the more liberal president.

The Washington Post succinctly summed up JFK on the 50th anniversary of the assassination as becoming “fodder for an interpretation industry toiling to make his life malleable enough to soothe the sensitivities and serve the agendas of the interpreters.” And who can argue with that?

Similar Articles

Resurgent Labour left will change the face of Birmingham politics 0

The Labour leadership and deputy leadership contest could have significant implications for Birmingham in the run

It’s yesterday once more with Corbyn set to lead Labour into the electoral abyss 4

I have no reason to revise my prediction that Jeremy Corbyn will be the next

‘Haunted by Kerslake, but Albert’s regeneration legacy will stand the test of time’ 16

Sir Albert Bore was clearly rattled by my article suggesting these were dangerous times for

Boundary Commission on Birmingham: An open letter from the chair, Max Caller 6

Chris Game raises some interesting and important points about the Local Government Boundary Commission for

Having misjudged the Boundary Commission, is the Council doing the same with the Chancellor? 18

Chris Game from the University of Birmingham asks whether Birmingham city council is about to