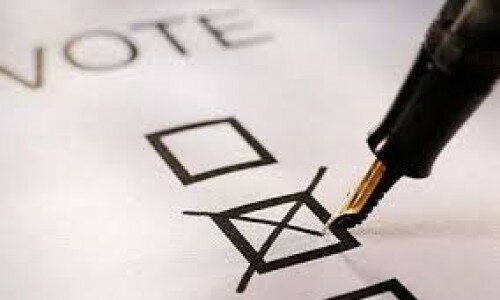

Why voter registration matters

In 1967/68, while attempting concurrently to write a PhD thesis (no!) and earn enough to live (just!) , I had the good fortune to work as a research assistant to the late Anthony King, well-known and respected Professor of Government, writer, broadcaster, and public intellectual, writes Chris Game.

Here, as the possibility of a second referendum or a snap General Election have not entirely disappeared, he looks at the development of electoral registers and the impact of their completeness on election results.

King, one of the two people who most shaped my so-called career, wasn’t himself really a ‘psephologist’ – a statistical analyst of elections and voting patterns – but he was seriously interested in such things, including voter registration.

As a Canadian, he was familiar with this being a federal (national government) responsibility relying (then) on huge numbers of enumerators canvassing door-to-door, repeatedly if necessary, to produce a national register highly regarded for both its completeness and accuracy – and thereby a complete contrast to the US’ almost entirely decentralised, and politicised, state-run process.

Knowing something of how the UK resembled the US in not just decentralising electoral administration but in our case to the lower-tier of often quite small councils, King was instinctively sceptical about both UK registers’ completeness and accuracy and about whether indeed these things were even measured. My mission was to find out.

In one sense it was easy. Two decades before the register-based poll tax/Community Charge was invented, over three before we had a national Electoral Commission, and over four before the arrival (outside Northern Ireland) of Individual Voter Registration, hardly anyone seemed exercised by either part of the question.

An erstwhile University of Birmingham colleague, Kenneth Newton, provided a pleasing illustration in his 1976 book, Second City Politics. After cautioning how high reported percentage turnouts can often be a product of low levels of electoral registration, he noted the “extraordinarily high proportion of adults on the electoral register in Birmingham” – over 99% in 1951.

Which he then contextualised, recording the council election office’s proud boast of how, while of course endeavouring to contact and encourage voters to return their annual registration forms, its policy was to keep as many names on the register as possible, removing them only when it was certain that they were dead or had moved.

Newton doesn’t say whether he inquired as to what would happen if the figure reached over 100%, as indeed it can and does (see below). But the unmistakeable point is that, even had they been measurable, the statistical accuracy and precision of registers were not in this era anyone’s serious priority.

It’s useful, though, to recognise what, for instance, the apparently impressive estimates of ‘96% completeness’ recorded in the occasional early research studies (see graph) actually meant. They were the percentages of electors found to have been registered at the correct address at the time of the autumn annual canvass the previous year.

However, by December, when the registers came into operation, the figures were already down a few percent, and, were an election held the following autumn, towards the end of a register’s life, the proportions of correctly registered electors would have dropped to around 86% – and significantly lower among younger potential voters, in minority ethnic communities, and in inner cities generally.

Then, in 1990, came the register-based Community Charge (‘poll tax’), followed swiftly by analyses of the 1991 Census suggesting that up to a million people (‘The Missing Million’) may have absented themselves from the Census returns.

The causes of this absenteeism were various, but clearly there were many who disbelieved – and with justification – that their councils’ electoral and community charge registers were as totally insulated as they were being assured. If voters behaved entirely rationally, they’d obviously never bother, but they’re not completely gullible either.

By this time there was growing interest in registers of all sorts, and that in 1992, with deliberate absentees from electoral registers and/or the Census being disproportionately Labour or Liberal Democrat voters, the outcomes of up to 10 parliamentary contests were likely to have been affected in a General Election the Conservatives won with a Commons majority of 21.

But it took the hugely overdue arrival of the Electoral Commission in 2001 and the 2003 introduction of Individual Elector Registration (IER) in Northern Ireland for the extent and composition of non-registration to be researched at all rigorously.

This is not the place – cue audible sighs of relief – for even a summary of that research, but the headline statistics from the Commission’s most recent work are those in the red box on the graph: local government registers assessed as 91% accurate and 84% complete, parliamentary registers as 91% accurate and 85% complete.

Unsurprisingly, highest levels of completeness were for those owning their property outright (95%), lowest for private renters (57%). And, more significantly in the present context, highest levels of completeness were for over-65s (96%), lowest for 16/17-year old ‘attainers’ (45%), then 18/19s (65%).

So, why am I bothering you with this stuff right now? Do I know something you don’t about an imminent snap General Election? No, but there are reasons.

First, you may have caught a , emanating from a YouGov survey for (surprise!) the People’s Vote campaign, about Britain “switching from a pro-Brexit to an anti-Brexit country”.

More precisely, on January 19th (‘Crossover Day’), if not a single voter in the 2016 Referendum had changed their mind, enough older, mainly Leave voters would have died – at a net rate of about 1,350 a day – and enough mainly Remain voters reached voting age, to wipe out the Leave majority.

By March 29th, our supposed ‘Leaving Day’, the Remain majority will have reached 100,000 – again assuming no mind-changing among 2016 voters.

I should explain that this whole eye-catching story was a characteristic creation of Peter Kellner, outstanding political commentator, also founder and former President of YouGov, and a tweeter.

And it so happened that the first discussion I had of this ‘finding’ was with someone who’d seen Kellner’s tweet and thought he’d spotted the mistake: that these first-time voters would have much lower registration rates than the dead ones did.

Silly billy! As Kellner’s full article notes, despite the evidence that these new “young voters are especially keen on a new popular vote” and that “among those saying they would definitely vote, the [Remain] margin is more than four-to-one, I have NOT counted any rise in turnout among the under-25s in my prediction”. So there!

Fascinating as this is, it lacks, as the Editor will have noted some way back, any conspicuous Birmingham/West Midlands relevance. And that’s because I’ve left to my climax the introduction of choropleth maps – which, in case you’ve temporarily forgotten, is a pretentious Greek-derived term for thematic maps in which areas are shaded in proportion to the measurement of the statistic being displayed.

The statistic here is Registration Proportion (RP), and – oh, Happy Days! – the Cabinet Office, in its evidently spare time, has just produced a whole – for our enjoyment, of course, but also to inform and support the democratic engagement strategies of Electoral Registration Officers and others.

There are lots of cautionary notes about the maps’ statistical limitations: how RP is a rough indicator, not a quality measure; that a low figure may simply reflect a large ‘ineligible’ population and should certainly not be used to evaluate or start sacking EROs, etc. But they do convey significant information and they’re certainly, in a nerdy way, fun.

Even accepting the qualifications, it was impossible not to be struck, in my main illustration, by the fact that our just seven WM metropolitan boroughs, covering not wildly differing socioeconomic areas and populations, managed to span all five of the Atlas’s register completeness categories.

None topped 100% – though, as noted earlier, it is possible and was managed, albeit by the highly atypical City of London – but Dudley made it into the highest category while Coventry were stuck in the lowest, with Birmingham only just ahead. That’s a 15% spread over something as vital as voter registration – and while you can debate its statistical significance, it’s surely hard to dismiss its democratic relevance.

Similar Articles

PM: gave unlawful advice; frustrated Parliament

"Scenes." As young people would say, writes Kevin Johnson. "Unlawful." "Unequivocal." "Historical." These words are not,

WMCA: Nothing to see here…move along

As the Prime Minister prepared to address leaders ‘up North’ gathering for the Convention of

HS2: new driver needed

Is the Oakervee Review "welcome", "frustrating" or the end of the line for HS2, asks

Dawn goes Down Under

It might appear that Birmingham city council changes its chief executives more regularly than its

Who can beat the Street?

You could be forgiven for not realising we are in the foothills of the very